Author’s Note:

These SCANCOS presentations of the Scandinavian Society of Cosmetic Scientists (SCANCOS) Conference, which took place in Helsinki, Finland, in November last year, summarized herein cover the meaning of borderline cosmetics in terms of definition, and definition within the context of cosmetic “claims”; the categories and types of borderline cosmetics and how they cross-over with other legislations; what case-by-case basis means; functions of a product versus claims; the need for robust evidence and how evidence may or may not be considered; misleading the consumer – perceptions and examples of case studies.

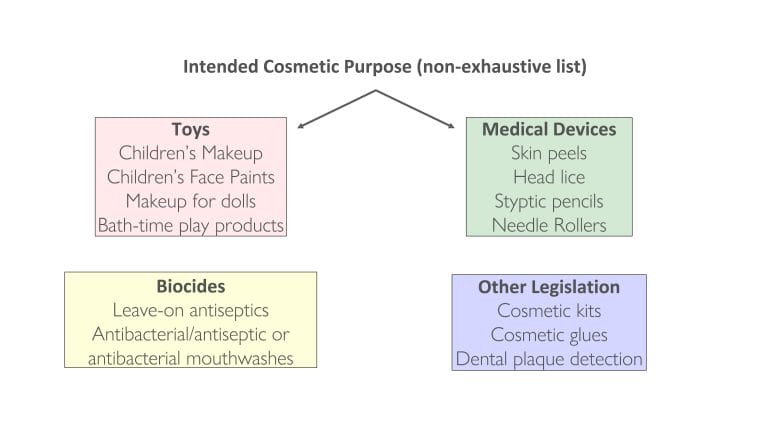

Intended Cosmetic Purpose

Introduction

It is essential that cosmetic brands understand the regulatory framework in which their product developments are classified.

More often than not, brands can find themselves facing a dilemma when it comes to such categorisations. A number of cosmetic products will overlap with either medicines, medical devices, foods, toys, and biocides. In the EU this overlap is termed “borderline”, especially when the classification of a “cosmetic” product is unclear. This means that brands need to be aware of the regulatory requirements of each of these categories when it comes to defining their “cosmetic”.

Challenges in evaluating and classifying products can even arise within the confines of the same legal framework. For instance, according to the EU Cosmetics Regulation 1223/2009, a

mouthwash making “antibacterial” or “antiseptic” claims could be classified as a cosmetic product, a biocide, or a medicine. If the product involves a device, such as implants, it may be categorised as a medical device. Determining the classification of these “borderline products” is made on a case-by-case basis in the EU.

Defining Cosmetic Products

A cosmetic product, as defined by the EU Cosmetic Regulation ((EC) No 1223/2009), refers to: “any substance or mixture intended to come into contact with the various external parts of the

human body, including the teeth and mucous membranes of the oral cavity”. Its purposes may include cleansing, perfuming, altering appearance, correcting body odours, or protecting and maintaining them in good condition. To classify a product as a cosmetic under this regulation, it’s intended purpose/function, formulation, and site of application must be clearly defined. For

example (Figure 1), children’s makeup, and face-paints actually cross-over with the Toys legislation (TSD 2009/48/EC), while skin peels and head-lice treatments fall under the medical device legislation ((EU) 2017/745 ), etc.

Primary functions of cosmetic products include altering appearance (such as makeup), cleansing, beautifying, perfuming, protecting, or correcting odours. Additionally, a cosmetic product may have secondary functions, such as biocidal or antimicrobial claims in oral hygiene products, or deodorants and some soaps, where the primary purpose remains cosmetic. When evaluating the function of a cosmetic product, various factors are considered, including the manufacturer’s intention, presentation, labelling, advertising, claims, mode of action, composition, and consumer perception. Failure to clearly allocate a primary or main function

to a cosmetic product may lead to its classification into a different product category.

Claims Pitfalls

In her keynote presentation, Theresa Callaghan shed light on the prevalent frustrations encountered by numerous brands and products when navigating what is commonly referred to as borderline legislation. She elucidated the concept of a case-by-case assessment, emphasising that products are evaluated for their classification as either cosmetic or non-cosmetic by considering a comprehensive array of characteristics. These include, but are not

limited to, the formulation, mode of delivery, site of application, purpose and objectives, branding, and supporting evidence. Furthermore, she underscored that the successful classification of a borderline product hinges upon developers taking into consideration

the broader context, including consumer comprehension and the relevance of both the product and its claims.

Additionally, she elaborated on the criteria that would classify a product as medicinal or pharmaceutical. For instance, if the product makes references to specific medical conditions like atopic dermatitis or eczema; compares itself to licensed medicines (which would be non-compliant with EU claims criteria regarding “Fairness”); utilizes product or brand names that reference medical conditions (such as “Acne Banish”); includes testimonials or reviews implying medicinal effects (such as a consumer claiming that a moisturizer “healed/cured their eczema”); cites medical or clinical research testing unrelated to cosmetics (like CBD and Parkinson’s for a cosmetic product); incorporates graphics or packaging that suggest medicinal uses; or includes irrelevant or noncredible endorsements by doctors or professionals; it would be categorised as medicinal or pharmaceutical rather than cosmetic.

In giving a wide variety of examples of national authorities (UK’s ASA, and Germany’s Wettbewerbszentrale) challenging product claims that fall in the “borderline”, Theresa also stressed the common denominator in all of them, i.e., the lack of “robust evidence” to support these claims. Robust (strong) evidence relies on the distinction between evidence strength and the security of an “evidence” claim, as well as the fallibility of assumptions that might be made regarding the reliability/quality of testing procedures. By providing more (solid) evidence, robustness can increase the safety and significance of an evidence (claim) assertion.

Intended Cosmetic Purpose – “Borderline” Pharmaceuticals

Choosing the Right Ingredients

The composition of a cosmetic product is closely linked to its function, with claims often based on specific ingredients within the formulation, such as fluoride in toothpaste for therapeutic

purposes. As Jari Alander indicated in his presentation, the choice of the right ingredient is essential, and their use and application will define which regulatory standard they will occupy.

Moreover, the safety assessment of ingredients is mandatory, and while the regulations can be in conflict, there is a need to focus on their application. Compliance with regulatory standards is essential; cosmetic formulations must avoid prohibited ingredients listed in Annex II of the EU Cosmetics Regulation, adhere to restrictions outlined in Annex III, and meet requirements for colorants (Annex IV), preservatives (Annex V), and UV filters (Annex VI).

Regarding application, cosmetic products are designed for external use on various parts of the body, including the epidermis, hair, nails, lips, external genital organs, as well as the teeth and

mucous membranes of the oral cavity. As for biocidal products, they contain active substances aimed at combating harmful or unwanted organisms, exerting control through destruction, deterrence, or rendering them harmless. The primary function, as indicated by product claims, plays a key role in differentiating between cosmetics and biocidal products. For instance, bath soaps boasting antibacterial or antiseptic properties fall under the category of biocidal products, while sunscreens, offering protection against UV radiation, are also classified as biocidal products.

Medicinal Products

According to Directive 2001/83/EC, a medicinal product encompasses any substance or blend with therapeutic or preventive properties for humans. This classification extends to substances

administered with the intent to restore, correct, or alter physiological functions through pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic means, or for medical diagnosis. For instance, while shampoo is deemed a cosmetic product due to its hair-cleansing function, an anti-dandruff treatment qualifies as a drug, as it targets dandruff through pharmacological action. Consequently, an antidandruff shampoo falls under both cosmetic and drug categories.

However, there are many other so-called cosmetic products which fall under the medicinal directives (Figure 2 ). These include cellulite, wrinkles, skin lightening, hair growth/reduction, etc.

In Japan, according to James Seguerra’s presentation, cosmetics and medical devices can potentially fall under an additional category of legislation known as the Quasi drug legislation. This designation applies to products designed for specific purposes such as skin lightening and anti-aging treatments. He also highlighted that while quasi-drugs can have a beneficial impact on the cosmetic category, navigating the regulatory landscape is complicated due to restrictions on claim wording. Unlike in the medical realm, cosmetics cannot make hard claims, posing a significant challenge for product marketing and consumer communication within this sector.

Natural Products

In his presentation, Mark Smith explained that with the ever-increasing popularity of cosmetic products composed of natural ingredients and a growing number of them making claims without

clear evidence or using non-compliant sustainability claims, compliant innovation becomes challenging. Moreover, natural products like Aromatherapy/Essential oils are considered borderline within the definition of legislation. Pure essential oils may be classified as cosmetics if they meet the definition of a cosmetic product and do not fall under the definition of medicinal products.

Sustainability, the use of natural ingredients, and reducing environmental impact are all increasingly important, but legal compliance in the market where you place the product is essential.

The role of ECOCERT was presented by Pauline Rafaitin.

Thanks to apps and social media, consumers are able to get more information on cosmetic products and brand commitment, but they are still vulnerable to misleading claims in a highly competitive market. That’s why, regulators are strengthening their constrains on brands and manufacturers to avoid greenwashing. She explained that as a certification body, ECOCERT plays his role of trust maker thanks to its independent third-party guarantee. For more than 20 years, ECOCERT has been interacting with the cosmetic supply chain to build strong and reliable certification standards, and Pauline presented this fact in the context of Greenwashing,

certification development and assessments, and building trust between the supply chain, brand and consumer.

Natural products commercial presentations were also given by the programmes sponsors SAFIC-ALCAN and Givaudan highlighting green chemistry for ceramides (Ecoceramides), and active ingredients from algae and micro-algae respectively.

Medical Devices

As per European Union Regulation (EU) 2017/745, a medical device encompasses instruments, apparatus, software, implants, reagents, materials, or other articles, whether used singly or in combination.

Essentially, a medical device is intended for human use in addressing diseases, injuries, disabilities, anatomical structures or functions, physiological or pathological processes, as well as other specialized medical conditions.

Moreover, this regulation covers certain products with aesthetic purposes, including equipment emitting high-intensity electromagnetic radiation, i.e., lasers and intense pulsed light devices

used for skin resurfacing, tattoo removal, hair removal, or other skin treatments. Additionally, this regulation encompasses specific products intended for aesthetic purposes. These include tinted

contact lenses, as well as equipment emitting high-intensity electromagnetic radiation, such as lasers and intense pulsed light devices utilised for skin resurfacing, tattoo removal, hair removal,

and various other skin treatments. Numerous medical devices are esigned for application to superficial parts of the human body. The key distinguishing factor of a medical device is its claim for medical use or classification within an aesthetic category, setting it apart from cosmetic products.

For instance, while a foot cream primarily used to moisturise dry skin qualifies as a cosmetic product, it would be reclassified as a medical device if it claims to heal damaged skin displaying

cracks or fissures.

In her presentation, Anna Larsson discussed that as cosmetic product developments continue to advance, new technologies, formulations and their appurtenant claims risk falling under the

definition of a medical device (or even a pharmaceutical product).

As with other speakers, she clarified the differences and similarities between cosmetic products and (mainly) medical devices, with special focus on the European Union, and explained how

development requirements of medical devices within EU are very similar to the FDA requirements of the USA.

Testing for Borderline Products

When testing for borderline product claims, the design of the study is key. In her presentation, Iryna Kruse stressed the importance of clinical studies, and that these are the best approach to

obtain credible, relevant and successful data for product claims.

Furthermore, she stressed that while there is a large portfolio of clinical methods and biophysical tools that continue to develop rapidly, clinical studies for claim support have to be scientific and results have to be based on advanced statistical evaluation. Moreover, good claim support relies on effective cooperation of marketing, research & development, lawyers and the investigator. Importantly, the claims that you develop can only be an interpretation of the scientific data achieved, and this is why the legislation demands robust evidence and claims based on the totality or body of evidence.

Main Points for Consideration

When developing products that potentially fall within the “borderline” category, it is crucial for brands to remain vigilant and stay informed about all relevant legislation, including the guidelines outlined in the borderline manual. In cases of uncertainty, consulting with market authorities such as the MHRA in the UK and the EU in-market control authorities is advisable, as each product and its claims undergo individual assessment on a caseby-case basis. It’s important to recognise the authorities’ rights to take necessary measures to determine the classification of a specific product or group of products as either cosmetic or non-cosmetic.

Furthermore, brands must exercise caution to avoid misleading or deceiving consumers, as any implications made in branding will be subject to scrutiny. The imperative for substantial

evidence applies to all cosmetic products, regardless of their classification as “borderline” or not. Studies supporting the evidential basis must be meticulously designed and relevant, and final claims should consider the broader context, consumer relevance, and understanding.

Conclusion

Incorrect product classification can have detrimental effects on businesses and pose significant safety risks for end-users if the intended product use or function is misconstrued. Direct consequences may include potential product recalls, label redesigns, reapplication or re-notification to competent authorities, product reformulation, or application for variation within the same regulatory framework. Additionally, there are associated costs, potential damage to brand reputation, loss of time, and other burdens.